Investing in UK opportunities

Where to look for stocks that appeal to investors in the UK

The UK equity sector has been somewhat unloved over the past decade as political uncertainty and questions over the economy have arisen.

But outside investors, particularly in the private equity industry, are seeing plenty of potential and are buying UK assets with relish.

So where are the opportunities? Oil and gas has especially fallen out of favour given goals of achieving net zero, but with soaring demand and rising inflation, these stocks have come back into favour.

There has been a recent rally, with sentiment shifting to value stocks over the past few months, driven in large part by rising interest rates and inflation.

There are still political uncertainties, both in the UK and in Europe more generally, given the war in Ukraine. What this means for the investor in UK stocks raises as many questions as answers.

UK equity allocation to see boost

More than half of the advisers who responded to our latest Despatches poll said they intended to increase their allocation to UK equities this year.

The poll shows that 58 per cent will either definitely or probably increase their exposure to the home market this year.

The poll found that 19 per cent of respondents are definitely increasing their UK equity exposure this year, while 38 per cent "probably" will.

UK equities have been sharply out of favour with investors over the past decade, due to a combination of political uncertainty and clouds over many of the sectors that dominate the index, such as mining, oil and gas and banks, and their viability in a changing world.

The start of 2022 was supposed to herald a new era, with the types of stocks that dominate the UK market rushing back into favour, and the technology and other stocks that have been in favour in the past, but are a tiny part of the UK index, falling.

And that is how the year began, with UK equities performing strongly, but the recent decline in market sentiment has seen the UK market underperform relative to the US.

The FTSE has performed relatively well amid the turmoil of 2022. (Source: Bloomberg)

The FTSE has performed relatively well amid the turmoil of 2022. (Source: Bloomberg)

Quality assets are available at cheap prices, says Laura Foll. (Source: Unsplash)

Quality assets are available at cheap prices, says Laura Foll. (Source: Unsplash)

It is a curiosity that while the FTSE has performed relatively well amid the turmoil of 2022, the Investment Association UK All Companies sector remains starkly out of favour among fund buyers, with the latest IA data revealing net outflows of £990m in March 2022.

In performance terms, the IA UK All Companies sector has performed slightly better than the IA Global sector on a year to date basis, losing 4 per cent relative to 6 per cent for the global sector.

The sentiment issue has been there since the UK voted in 2016 to exit the EU, says Robin West, UK equity fund manager at Invesco.

He says the uncertainty of that event and its aftermath meant that UK equities were “shunned” by investors, but he says that the relative stability since a trade agreement was reached means investors are starting to look again at the UK market – albeit those investors tend to be from private equity funds rather than advised clients.

However, he feels this validates the view that many parts of the UK equity market are undervalued.

Laura Foll, joint manager of the Lowland investment trust, says there has been an element of “self-fulfilling prophecy” in the performance of the UK equity market in recent years.

She says: “The market underperformed so people reduced their allocations to the UK market, which led to underperformance.”

Foll adds: “The discount at which the UK market is operating may not be because there is a structural problem with the market. If there was a structural problem, then it would the case that it would focus on some sectors, for example retailers, but the fact that all of the sectors of the market are trading at a discount to the rest of the world tells you it’s a sentiment issue, more than a structural problem.”

Neil Veitch, a UK equity portfolio manager at SVM, says "I would love to be able to say the recent outperformance of UK shares compared to other markets has led to a sentiment shift, but it hasn’t really.

"That’s because the UK market rally has been driven by a tiny number of shares, in the oil and mining sectors, plus HSBC and AstraZeneca. It has been a very one-dimensional rally."

Many investors highlight the relative lack of successful large technology companies on the UK market as a reason for the structural issues, and for most of the past decade technology and other long-duration assets – that is, equities which are often called growth stocks – have performed well, but the UK market has a predominance of value stocks, and so was on the wrong side of market sentiment for most of the decade after the financial crisis.

The market underperformed so people reduced their allocations to the UK market, which led to underperformance

But higher interest rates and the potential for higher energy prices means market sentiment moved away from the growth stocks and towards the value stocks, and Veitch says this, rather than any deep structural change, is the reason for the recent relatively strong performance.

He says: “If there is a resolution to the Ukraine crisis soon, then I would expect that energy prices would moderate, and the UK market would start to underperform relative to the rest of the world.”

Foll is also wary of predicting that the sentiment shift of the past decade will fully reverse. She says many UK wealth managers have reduced their clients allocations to the home market in the name of diversification, and while cyclical factors may mean there is some increase in allocations in future, she does not anticipate wealth managers ever restoring clients' overweight exposure to the home market back to previous levels.

However, a rally boosting a small number of stocks and longer-term factors may dent demand for shares listed in the UK in the long term.

The scale of this concentration is demonstrated by the fact that, in the first three months of 2022, the FTSE 100 outperformed the FTSE 250 by 16 per cent.

Richard Bullas, UK mid-cap fund manager at Franklin Templeton, says the reason for this relative underperformance by companies outside of the FTSE 100 is that investors have reacted to recent world events by turning to more defensive stocks, and there tends to be more of those among the large caps.

He says the FTSE 250 derives about 30 per cent of its revenue from the retail sector, an area that is both structurally challenged from the rise of e-commerce and cyclically challenged by higher inflation and the recent downward revisions to UK economic growth forecasts by the Office for Budget Responsibility.

But he notes that while there is validity to the argument that there are more safe havens among the large caps, he adds investors' determination to reduce risk levels in their portfolio means they are also “masking where some of the opportunities lie”.

He cited the recent sale of wealth management business Brewin Dolphin for a 62 per cent premium to its resting share price as an example of companies that are being under-appreciated by the market.

Private parties

A feature of the UK equity market over the past five years has been the number of private equity businesses acquiring UK-listed companies, though this is also a feature of equity markets generally.

There are three reasons private equity funds have been able to grow their assets under management substantially over the past decade.

The first is that low interest rates have led some investors to increase their exposure to alternative assets. The second is that those low interest rates of the past decade were generally beneficial to stock markets, causing equity markets to trade at record highs, and prompting many investors to seek returns in private companies. The low interest rates also make it cheaper for private equity businesses to borrow.

Most of the acquisitions they make combine equity capital raised from investors and debt – low interest rates make the cost of the debt lower, and so make the returns achieved by some companies look more attractive.

Foll says the fact private equity businesses are buying UK-listed companies in such volume also indicates that it is possible to find attractive companies in the home market, and adds that when they do an acquisition, they tend to pay a price far in excess of the share price at which the acquired company is trading on the stock exchange.

Foll says the fact they are prepared to pay such a premium shows quality assets are available at cheap prices.

While volatility can create long-term opportunities, it may be a little early to go further down the market cap scale

But she says those opportunities tend to be outside of the FTSE 100.

She adds many investors view the UK as primarily an income-focused investment, which means a focus on the FTSE 100, neglecting small and mid-caps, and so creating the opportunity.

This is a point taken up by Mark Denham, head of European equities at Carmignac, who says that the FTSE 100 is full of companies that may have benefited from the recent rotation to value, but he thinks those operating in areas such as mining and oil are unattractive both because of their cyclicality and as a result of long-term trends around sustainability.

This means many investors may not wish to own those companies in future, creating a long-term reason for those share prices to struggle.

Denham is primarily focused as an investor on large caps, and has found some stocks he views as attractive within that part of the market, but is wary of investing in small and mid-caps now given the health of the economy.

He says: “We would say that, in the near term, concerns about the impact of rising interest rates on stock markets and a heightened risk aversion will probably restrain the performance of smaller sized listed companies. So, while volatility can create long-term opportunities, it may be a little early to go further down the market cap scale.”

Ben Needham, manager of the Ninety One UK Equity Income fund, says large caps have been performing very well as a result of both cyclical factors and also investors liking the liquidity of the FTSE 100, giving them a short-term way, although he says that over the longer term the returns from the large cap index have been more mediocre relative to the small and mid-cap market.

He is looking at companies in the small and mid-cap area that sell products in areas such as medical devices, which have low levels of debt, and which do not need lots of extra capital in order to be able to expand.

He says when interest rates were very low, the market did not care very much about debt levels, as debt could be funded very cheaply, but with higher interest rates afoot, the market will now be very wary of companies with high debt levels, even if they are performing quite well.

Franklin Templeton's Bullas is keen on the house-building sector, which he notes has fallen from favour, with investors worried about the impact of higher interest rates on house prices – the cyclical concerns highlighted by Denham – but he says the housing market remains robust and that this is an area where structural growth is strong, and cyclical factors are causing negativity now.

Seb Jory, fund manager at Tellworth, says that while many are very focused on the negative impact of present economic conditions on consumer-focused stocks, he is also concerned about the impact on industrial and financial sectors.

He says that many industrial companies responded to recent supply-side issues by increasing their stock inventory, but now, with economic demand declining, may find they have too much stock rather than too little.

Such a scenario would be quite disinflationary, and he says there has been a shift within the UK market in recent weeks, with defensive stocks now being prioritised over more cyclical assets.

David Thorpe is special projects editor at FTAdviser

House View: Oil and gas stocks – no easy answer

In recent years investors have actively avoided stocks in oil and gas companies because of their unfavourable environmental, social and governance credentials. This approach was tacitly supported by governments as they promoted investment in environmentally friendly energy sources.

As a consequence, energy companies drastically cut capital expenditure on new oil and gas fields. Seeking a drive to net zero, they instead directed money towards renewable energy projects, paying down debt and returning capital to shareholders.

Meanwhile, universities began dropping courses for the oil industry, squeezing the labour supply. In 2010 there were roughly 2,000 graduates from petroleum engineering; last year there were around 200.

Avoiding oil stocks has not hurt investors – until recently. But lack of investment by the industry has led to a critical fall in production capacity and supplies just at the point when global recovery has picked up. So even before Russia made itself a global pariah, the scene was set for an upturn in the oil price.

Supply and demand

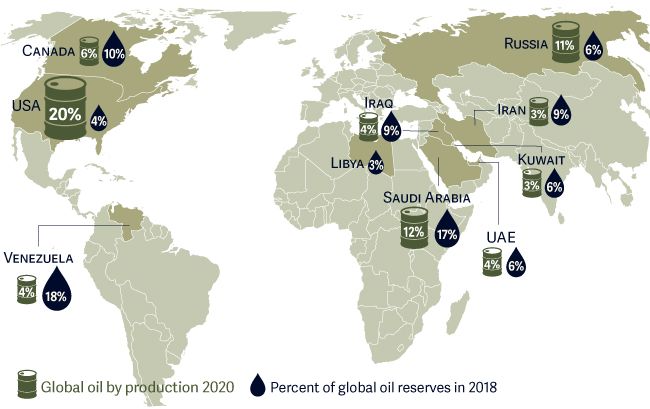

Global supply in Q1 2022 (including Russia) was approximately 98mn barrels per day (mb/d). At the start of 2022 Russia exported 6.5 mb/d, and it is estimated that two-thirds of this output (3-4 mb/d) will be lost due to ‘self-sanctioning’ – effectively bringing global supply closer to 94 mb/d.

To avoid elevated prices, we need demand to be around 2 mb/d less than capacity. But demand is expected to rise to 100 mb/d by the end of the year with the recovery in global aviation. And JPMorgan has estimated that by 2030 global oil demand will be nearer 107.5 mb/d.

This helps explain the crisis we are facing and why policymakers and investors are rethinking their attitudes to oil and to gas in particular.

No quick fixes

The oil companies can step up their investment in new production capacity to help make up the deficit. Saudi Aramco, for example, says it could increase production by 1 mb/d. But these projects take four to five years to bring online. What can be done in the shorter term?

One solution is to increase supply from other major players. Iran and other countries in the Middle East could up production. Venezuela, which holds the largest oil reserves in the world, has already increased output, and it may be possible to bring in new capacity from Texan shale fields in about a year – but their combined effect will be marginal.

There are also oil reserves. The Middle East has c1.5bn stockpiled oil barrels that could be released over the coming year. The International Energy Agency also holds c1.5bn barrels, or 750m ex the US, and is now looking to release 1mb/d for 180 days. It is highly doubted whether more will be forthcoming.

Fossil fuel companies – problem or solution?

Recently ESG in the oil sector has frequently been thought of only in environmental terms. But another compelling point is becoming evident: higher energy prices have a social cost.

Forcing voters to choose between food and fuel is politically unpalatable, to say the least. Voters and consumers have bought into the need to move to net zero over the longer term. In the near term, however, there may be forgiveness for a suspension of targets if it reduces dependence on Russian fuel and brings down elevated energy prices.

We are seeing a change in the political rhetoric. For instance, the new British energy strategy speaks of a licensing round of new North Sea oil and gas projects, planned to start this autumn.

Just as telling, the new EU ESG taxonomy looks set to redefine gas as a green energy source – recognition that gas is much cleaner than oil and has a vital part to play in the transition to a low-carbon world. Since 50 per cent of Shell’s production is gas, this could earn it a ‘green’ designation almost overnight.

Investors may begin to give more credit to companies working hard to improve their ESG credentials. For instance, Shell’s CO2 emissions last year were down 18 per cent versus their 2016 baseline, and BP’s were down 37 per cent against their 2017 baseline – and this is at a time when global emissions have risen.

A choice to be made

The oil giants face a dilemma. The UK and Europe need additional gas infrastructure, but who is going to pay billions for it? In the first months of the year the continent did not want gas, now it does. It is hard to make 10-year decisions on that.

Investing to increase production should bring down prices, but this will slow the progress towards ESG targets if done at scale.

Meanwhile, the cost of capital will need to fall to incentivise them to stop buying back shares and put more capital to work in both green/black energy sources to solve Europe’s problems.

It has been easy to knock the oil majors from an ESG perspective in recent years. Investors and policymakers may now be coming to realise they need to be seen not as the problem but as part of the solution.

Ambrose Faulks is co-manager of the Artemis UK Select Fund